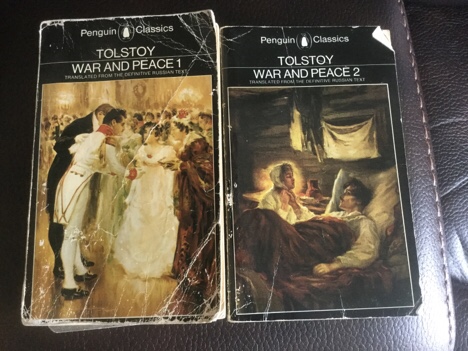

I read this masterpiece many years ago and reread it recently. My copy is the Penguin Classics two volume edition translated by Rosemary Edmonds, published in 1957. But when I grew weary of squinting at the faded size ten font printing I checked out the ebook edition from the library. This was translated by Aylmer Maude and Louise Shanks Maude and is the Duke Classics edition published in 2012, in a clearer larger font. It is quite different, including being organized into 15 Books plus two Epilogues, comprising 384 chronologically arranged chapters. I will stick to the arrangement as in the ebook.

Probably no novel, unless one considers the Christian Bible to be an historical novel, has ever been more throughly dissected and analyzed so I am not sure my review will contribute much, but I carefully avoided reading any reviews or Coles Notes to avoid forming biases or inadvertently plagiarizing ideas.

Starting off in the Petersburg and Moscow high society drawing rooms, the discussion about Napoleon’s 1805 invasion of Eastern Europe gets heated, with divided loyalties; the princes and counts vie for positions in the royal entourage, the cavalry, the diplomatic service and the army. At the end of Book 1, the timeless emotional farewell of soldiers leaving their families for the front is captured beautifully as Prince Andrew (known as Andrei in the earlier edition) bids farewell to his ailing crotchety father, Prince Bolkonsky, his lonely spinster sister and his pregnant wife. And globally, rigid military hierarchies, drills, and disciplines (in peacetime) seem to have changed little between 1805 and my experience as an army cadet in the 1960s.

In Books II and III the disorganized horror of war at the front is graphically detailed when the Russians and Austrians engage with the French concluding at the battle of Austerlitz, and captured Prince Andrew is wounded. This is after his father has unsuccessfully tried to marry off his ugly daughter (Andrew’s sister), on the home estate. It will be impossible for modern readers to keep the characters straight, especially with their numerous patronymics, and diminutives, but it is not really necessary to do so with the pitched battles and the blood of abandoned wounded and dead soldiers and horses mixing everywhere documenting the horror.

Book IV details the high society Moscow life with soldiers on leave, love triangles, gambling, dancing and intrigue, and a duel fuelled by accusations of stained family honour.

In Book V, Pierre compares his life to that of a useless screw with stripped threads, falls into a trance-like state under the influence of charismatic Free Masons as they hustle him through the secret initiation rites. (It is debated whether or not Tolstoy was a Free Mason.) And I, while training in the late 60s in a military hospital, became familiar with the triage by rank rather than by urgency of need or severity of illness as it is described by Count Rostov here.

In Books VI and VII, Prince Andrew experiences a bout of classic depression without naming it thus. The peacetime dinners and balls in the high society circuits of Petersburg are filled with intrigue and the counts, princes and princesses vie for recognition and esteem. As in modern society, elites in boxes at the opera are there more to be seen than to see the performance, but it is once again difficult to keep the characters straight. I had great difficulty relating to the hyped enthusiasm of a horde of hounds chasing down wolves, foxes and hares on the estates of aristocrats.

In Book VIII Tolstoy gives us an accurate and poignant description of Alzheimer’s disease in the aging Prince Bolkonski, fifty years before Dr. Alzheimer described the disease that bears his name. The charming, seductive, completely amoral Anatole may present the best description of psychopathy before the term was invented (in German originally), twenty five years later. Tolstoy, it seems, understood more about mental illness than his German contemporary Freud, even giving us a vivid description of hysteria (or conversion reaction in modern psychobabble), and anorexia in the sexually frustrated distressed Natalia.

Book IX includes eloquent discussions of fatalism, the placebo effect, and the nature of heroism but two quotes about Napoleon as he reinvades Russia in 1812 stand out: “Nothing outside of himself had any significance for him, because everything in the world, it seemed to him, depended entirely on his will.” And a little later: “ …he had long been convinced that it was impossible for him to make a mistake and that… whatever he did was right, not because it harmonized with any sense of right or wrong, but because he did it.” Remind you of any current politician?

In Book X, retrospective analysis of historical events as recorded by the winners is exposed for its flimsiness and biases, fatalism is re-examined, the gory details of the one day battle of Borodin is detailed, and Prince Andrew is mortally wounded. A keen insight as relevant today as in 1812.

In Book XI, the vagaries and errors of historians’ explanations of events is thoroughly ridiculed with careful analysis of the whole Napoleonic campaign in Russia. Tolstoy clearly understood the difference between correlation and causation and the folly of equating them.

Book XII deals with the chaos of the Russian’s abandonment of Moscow to the advancing French army, the destruction of much of Moscow by lawless incendiaries, and the touching scene of Natalia reconciling with her wounded and dying former fiancé Prince Andrew as they flee the conflagration of Moscow. And the show trials of captured Russian soldiers with the predetermined verdicts is as old as war itself. This book ends with the touching scene of Prince Andrew’s slow painful death so remarkably captured on the cover of one of the editions.

In Book XIII, Tolstoy’s cynicism of historians’ retrospective explanations of events is tied into his belief in fatalism, and with biting sarcasm ridicules the usual armchair historical account of Napoleon’s retreat.

In the final book, Tolstoy’s astute analysis of the whole war uncovers his biases in praising the disgraced Russian general Kutusov who tried unsuccessfully to restrain the Russian army’s slaughter of the retreating freezing French in the winter of 1812-13 and ridiculing the bungling Napoleon.

In Epilogue I, Tolstoy casts scorn on the conventional interpretation of historical events musing about the inevitability of subsequent historical developments up to 1850, and manages to pair off the remaining members of the main elite families in an unpredictable but uncontrived way.

Epilogue II consists of a very confusing treatise on what can broadly be defined as political science and the problem of free will that has plagued mankind for millennia, which could only be of interest to someone like Francis Fukuyama or moral philosophers.

Scattered throughout this whole tome are existential discussions about the meaning of life with clarity and insights that at least equal the later musings of Kant, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Camus.

There are more than the usual number of spelling, grammar and punctuation errors in this edition, as though the translators, copy editors and proofreaders relied entirely on an early-version computer spellchecker with no training in grammar or contextual sense. For example, in several places the word bad is substituted for the word had, several sentences have no verb, and the ranks were drown up rather than drawn up. A few maps of the relevant regions would have been a useful reference for this geographically challenged reader.

My wife thinks I reread this just for the bragging rights, but I really enjoyed it. With a few more rereads, I might even be able to keep the main characters straight.