Set largely in sparsely populated rural Nebraska in 2002 and 2003, this epic tale is centred on the life of a young single meat-packing plant worker who is severely brain damaged in a car accident. But the undercurrent of the harm that humankind is doing to the environment, in particular that of the Platte River wetlands and the migratory route of the Sandhill cranes is never far from the surface.

When the accident victim emerges from a coma, he has developed the rare Capgras syndrome, refusing to recognize his beloved visiting worried sister, believing her to be a planted substitute sent by evil forces to harm him. This morphs into Fregoli syndrome and then Cotard’s syndrome in which he insists that he is dead. He develops very elaborate explanations, believing that the caring distraught sister is an imposter, and expansive paranoid delusional conspiracy theories for everything that is going on around him. The contradictions and cognitive dissonance of these absurd beliefs mimic those of many apparently otherwise sane individuals and fringe religious cultists in our present society.

When the distraught sister persuades a famous New York neuroscientist (clearly modelled after the late Dr. Oliver Sacks) to assess her brother, he gets too involved, doubts the value of his previous popularization of modern neuroscience discoveries and sinks into depression and self-doubt. The mishmash of rare brain disorders readers are introduced to via his musings and lectures include hemispatial neglect, agnosia, prosopagnosia, asomatognosia, hypnopomia, Fregoli syndrome, Anton’s syndrome, reduplicative paramnesia, Charles Bonnet syndrome, pain asymbolia, ideomoter apraxia, and Cotard”s syndrome. I was aware of some of these, but not all, having researched aphasia, neologistic jargon, and echolalia in stroke patients early on in my medical residency. I was a bit surprised that the misphonia that one of my granddaughters has and that affected Winston Churchill was not included. And it seems to me that the not-very-rare synesthesia, wherein people see sounds, hear colours and taste shapes would be a great tool for any imaginative novelist to use.

The eternal conflicts between nature conservation and urban development are artfully exposed and explored as romantic entanglements develop between various individuals on different sides of the conflict. Deep philosophical questions about the nature of consciousness and what the word self means are discussed peripherally but, per force, remain unanswered.

The writing is engaging with vivid imagery, (“quivering like a Parkinson’s guy on stilts in an earthquake”), although the scattered nonsense neologistic jargon words in the opening paragraphs of early chapters, (seemingly designed to mimic the chaotic thought processes of the brain-damaged victim) may just be confusing to some readers.

When the Sandhill cranes are descending to the river at dusk. “ Another thread floats down on the still air. Then another. The fibre of birds catch and join, an unravelled cloth coming back together.”

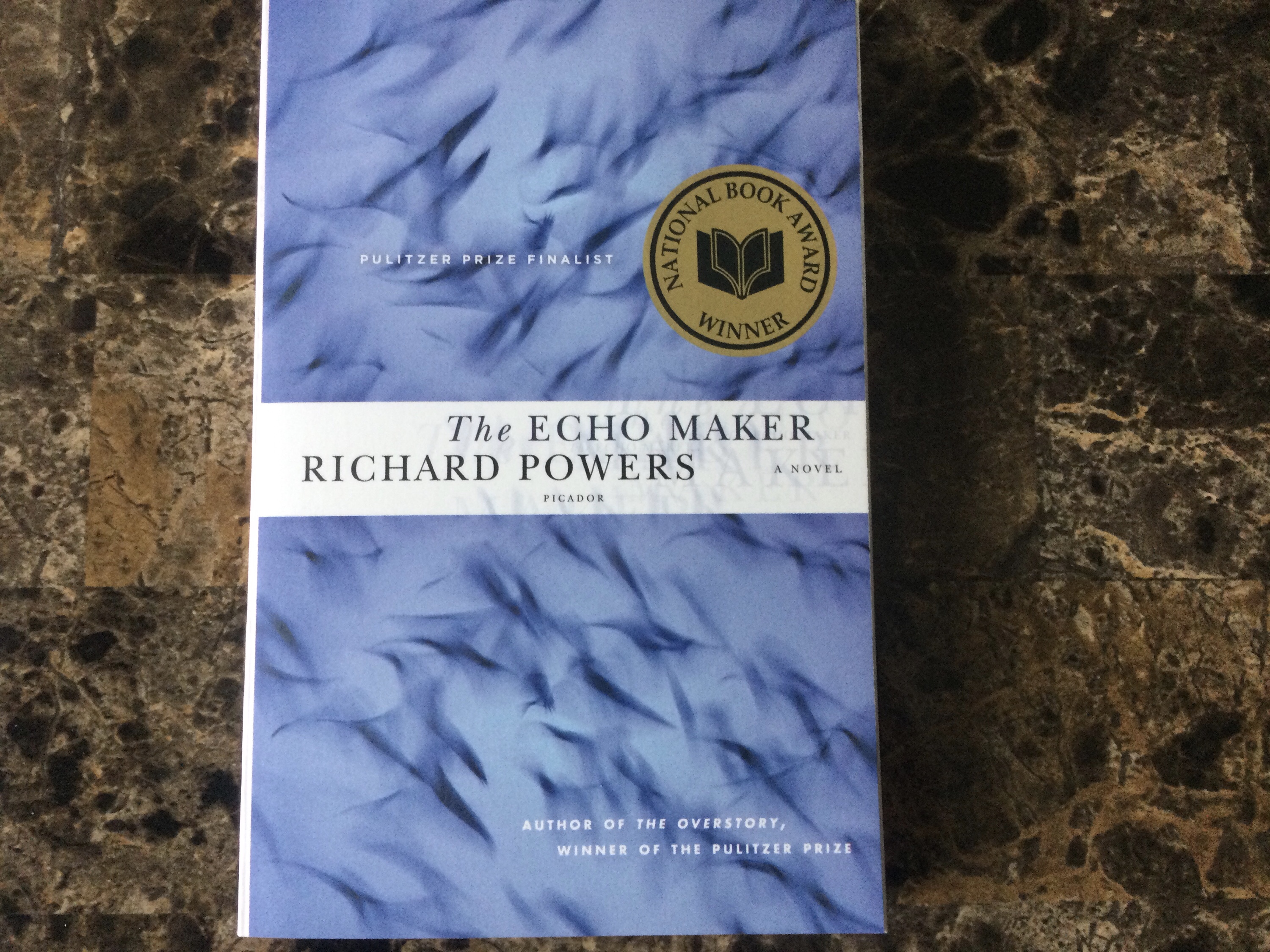

The deceptive “By the author of The Overstory” on the cover invites a comparison. This is a shorter good read, but neither the plot nor the characters are as realistic as in that later (2019) opus magnum, one of my all-time favourite novels.

Thanks, Alana.