Perhaps as a way to help the old man develop at least a rudimentary understanding of her chosen field of study, my Professor of Economics daughter sent me this book for my birthday. Or perhaps she just wanted to humble and torment me, knowing that I would read all of any gifted book. She succeeded if the latter was her intention, but not if it was the former.

The arrogant claim in the Preface to be as important as The Wealth of Nations, Das Kapital, The Rise of the Western World, and Guns, Germs, and Steel and the equally self-promoting wording on the author’s website ( “ I am a distinguished Professor..”) is off-putting, as is the very frequent references to his earlier publications in the footnotes.

If I even dimly understand where Clark differs from other economic historians it is in his emphasis on social Darwinism (survival of the richest) accelerating British fertility in leading to the Industrial Revolution, which was also much more gradual than commonly portrayed. And he lays claim to the assertion that it is primarily inherent inefficiencies in labor capital utilization that has lead to the modern great divergence in economies since the 1800s, with the attendant explosion of wealth inequality.

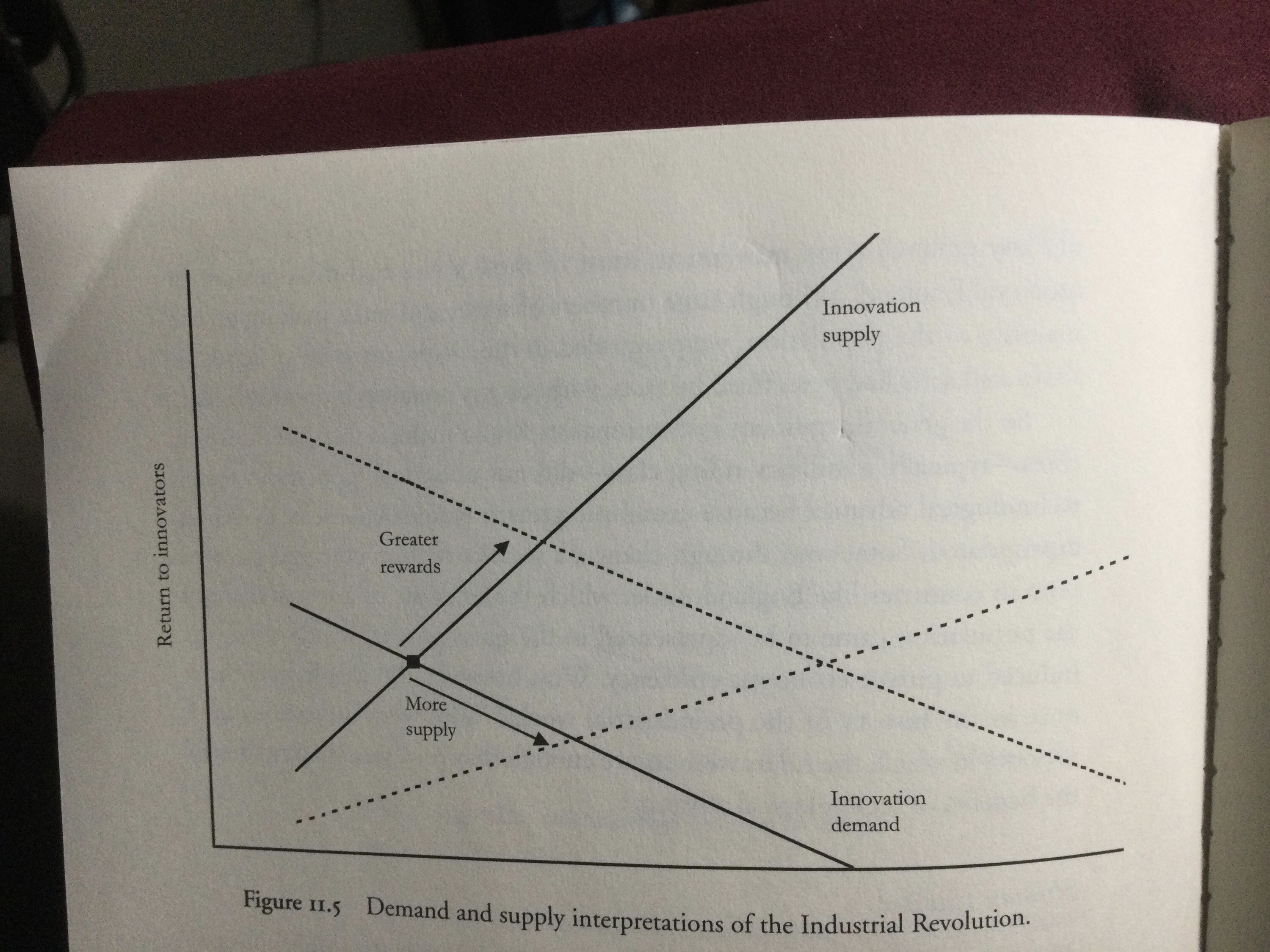

I have never been very adept at mathematics and never studied calculus, nor did I ever gain much understanding of actuarial science. When doing research I usually relied on professional statisticians to calculate statistical significance. But I recognize pseudoscience when I see it. Here I encountered dozens of charts and graphs that are purportedly important yet are unaccompanied by any measures of statistical significance, obviously equate correlation with causation, and were just plain confusing, as the one I chose to reproduce here shows.

What can this obfuscation possibly signify? There are apparently arbitrarily selected bits of sociological data from arbitrary time periods to reinforce what seem like arbitrary forgone conclusions.

Clark heaps scorn on the policies and actions of economists at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, apparently solely able to see the right way forward. And ironically his distain extends to academic economists although he is the Chair of the Department of Economics at USC, Davis. But like almost all economists, the holy grails that he never questions are the imperatives of productivity growth, consumerism, and ever more resource extraction, which is not compatible with our longterm survival in the age of global warming. GDP is apparently the only deity worthy of any worship.

For dedicated students of cultural anthropology, this could be considered a reasonable complementary document to Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Noah Harari’s Sapiens, and Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order, all of which I enjoyed reading, if it were not riddled with personal biases and criticism of previous works.

There are probably some profound insights and truths here that I failed to grasp, and it would be extremely presumptuous of me to dismiss this work entirely or to pretend that I understood most of it. To be fair, the references to other researcher’s findings is vast. The abundance of revelations of interesting, often counterintuitive historical facts was enough to keep me engaged. But I am sure that I flunked if this was my Introduction to Economics course.