First a note about the length of a book. My downloaded library edition of this one is listed as an intimidating 1736 pages! But that includes close to 700 pages that are not text-i.e. dedication, 165 pages of endnotes, a 220 page index, and at least 70 pages of colour photographs. So I calculated that there are about 1059 pages of text, to give my readers a rough idea of the time they need to set aside to read it.

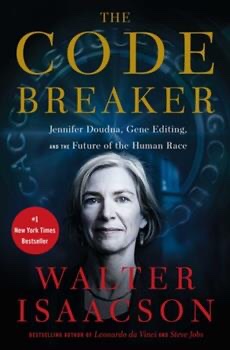

The author, a Tulane professor of history, has written biographies of such public figures as Henry Kissinger, Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin, and here focuses on the life of the 2020 chemistry Nobel prize winners, Berkeley’s Jennifer Doudna, and to a lesser extent her Pasteur Institute French collaborator who shared the Nobel prize, Emmanuelle Carpentier. But it expands to include many others who work in the same fields of genetics and the biochemistry of DNA, RNA and the codes of life on earth, including such forerunners as James Watson, George Church, and a host of other notable researchers and innovators around the world who collaborate and compete to unravel the secrets of life.

The major focus is on the 2012 discovery and subsequent applications of the awkwardly named CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) that bacterial DNA uses to fight off attacks by viruses. The far-reaching potential applications of these complicated genetic systems include the human gene editing ability to treat various genetic diseases such as sickle cell anemia and Huntington’s Disease. But it also has the potential to modify almost anything about our genetic makeup, with the ability to cut and splice our DNA with precision to enhance certain traits and eliminate others. The prospect of doing so in germ cells within embryos leads to the prospect of parents choosing to design babies with characteristics they deem to be desirable. Such a manoeuvre by the disgraced, now jailed Chinese researcher He Jainkui led to universal condemnation, but there is no doubt that the ease of using CRISPR technology will be applied in the future in many controversial ways. The author quickly learned to do CRISPR gene editing using readily available materials, implying that almost anyone could do so with good or evil intentions. The discussion of the use of genetic engineering to combat Corona viruses and similar threats is enlightening and highly relevant.

I cannot claim to understand all of the biochemistry and technology detailed here, but it is relatively easy to grasp the potential consequences. When used in somatic cell lines, CRISPR methods have the potential to ease the misery of thousands of sufferers who have lost out in the gene lottery. When used in germ cell lines in embryos, it could permanently remove some traits from our gene pool, potentially decreasing diversity and increasing inequality as rich parents design their offspring. Such controversial topics are analyzed in thoughtful philosophical thought experiments. In the July 3rd issue of The Economist’s annual What If speculations, by 2029, a worldwide group of biohackers are using designer RNA molecules on themselves to enhance alertness, prevent baldness, increase intelligence, muscle strength and endurance, and to even experience transient drug highs. Such possibilities are not now totally beyond the pale.

The author interviewed many scientists working in this field around the world. He is laudatory of Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Carpentier but also provides a balanced portrait of most of the other researchers, some of whom were bitter foes in patent wars, and races to be first to report discoveries. The no-filter bigoted musings of octogenarian James Watson are balanced by acknowledgement of his past accomplishment in working with Francis Crick and the less acknowledged Rosalind Franklin to determine the structure of DNA.

This book will instil awe of the complexity, intricacy, and fragility of the natural world in even the least scientific reader. A brilliant close friend, Dr. Al Dreidger, always gives me similar feelings of awe with his monthly Brainworm musings, his latest being about how only one genetic switch activated on day 36 of embryonic life, providing a methyl group to one end of one particular protein is the only thing that results in any babies being morphologically male. But for a strategically placed CH3 group one day in the fall of 1944, I could have been a super strong XY female athlete.

This is a difficult read, but well worth persisting with.

Thanks,

Floyd