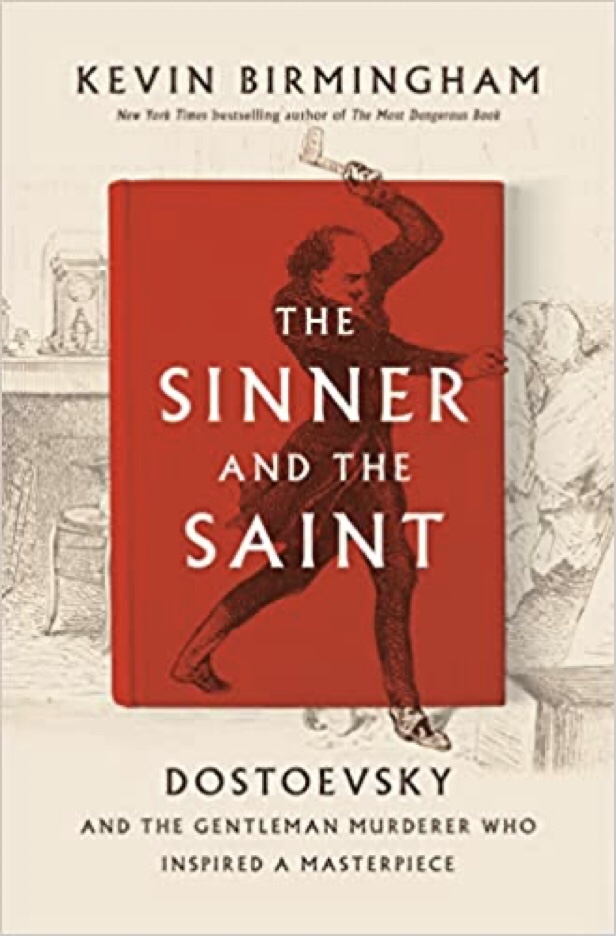

Had I not read and greatly enjoyed most of the nineteenth century Russian classics by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leon Tolstoy, and Ivan Turgenev, I would not have even looked at this most recent biography of Dostoevsky by a Harvard English lecturer. The son of a military physician murdered by his own serfs, Fyodor, a reckless gambler, and from an early age debt-ridden and phlegmatic, uniquely rejected his inherited status to become a writer when almost all Russian writers were hobbyists with other occupations. And he seemed to be always fascinated with murderers, trying to get into their heads.

In 1848 and 1849, as protests against autocracy rocked European capitals, 28 year old Dostoevsky, as part of a secretive intellectual cabal of liberals, anarchists, and atheists known as the Petrashvsky Circle, who advocated for freeing serfs, democracy, and women’s right to vote, was arrested and imprisoned in St. Petersburg after being betrayed by spies in their midst. After imprisonment and a staged last minute reprieve from execution, he was banished to a Siberian hard labour camp in Omsk for four years and forbidden to write. His fellow prisoners included many murderers but also some whose crimes were nothing more than crossing themselves in a way that the Orthodox Church found objectionable. There he observed many murderers firsthand, secretly scribbled notes, and studied the character of murderers to include in later writings.

Following his release by the new, more liberal reformist tsar Alexander II, successor to Nickolas II, he served five years of compulsory military service. (This would be during the Crimean War, but it is not clear whether or not he served there.) He married a widow suffering from tuberculosis in 1857, but their relationship was never a happy union. He became obsessed with reports of the famous Paris poet cum gruesome murderer Pierre-Francois Lacenaire with his numerous aliases and his horrific senseless 1835 murders, and this polite and charming criminal became the model for Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, in Crime and Punishment. There is no doubt that Lacenaire was a psychopath, long before the term was invented and the condition was accepted as a disease. He showed no remorse and intense distain for all societal moral standards. Now it is known that psychopaths have peculiar anomalies in their brains’ motor neurone networks. Is this the cause or just an effect of their behaviour? But at his trial, Lacenaire’s murders were described as being the result of a disease, of a ‘sick mind’.

The narrative alternates between the events leading up to Lacenaire’s execution and the intermittent destitution, gambling addiction, and affairs of Dostoevsky. His. poverty and threats of debtor’s prison was particularly acute during his three month tour of Western European cities in 1863 when he began planning the plot of Crime and Punishment, and again before it appeared in serialized form in a St. Petersburg magazine in 1866.

Dostoevsky’s outlook and beliefs varied from atheism and nihilism to materialism and Epicureanism at different times but he was never happy for long and was often profoundly depressed. His musings about the impossibility of free will and predestination are given scant attention in this tome.

The frequent premature deaths from infectious diseases including those of his first wife, his brother, and his nephew weighted heavily on him. The quackery of phrenology is described in detail and the unpopular but lucrative Russian pawn broker industry is also given great attention. It is no accident that they were the victims in both real and fictional murders.

The description of Dostoevsky’s frequent temporal lobe seizures with their religious epiphanies, similar to those of St. Paul and the Prophet Mohammed, is graphic although how Birmingham determined that they originated in his left temporal insular cortex is not clear. But they are also featured in his later The Idiot, one of his best short books, in my opinion.

This is not just a biography, but a primer of 19th century Russian history, societal norms, politics, and geography. The horrible conditions Dostoevsky describes in the Siberian prisoner labour camp in Omsk reminded me of those described by Alexander Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago and his One Day in The life of Ivan Denisovich, a century later. Russian rulers have a long history of treating their citizens horribly to this day.

This biography ends at his marriage to his much younger stenographer in 1867, long before he wrote the masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, in 1880, featuring more murders.

For dedicated Dostoevsky fans, this provides interesting reading. But it is also windy and needlessly long, including a lot of irrelevant detail. Birmingham lacks the word smithing skills of his subject, even though I could only read the latter in translation. In addition the hard copy library edition is written in a small font with fainter than usual print on off-white paper. If you want to delve into it, get the available audiobook- the absence of the unhelpful jumbled index will be no great loss. The audiobook has the additional advantage of helping with pronunciation of the difficult Russian patronymics.

Thanks,

The New Yorker.