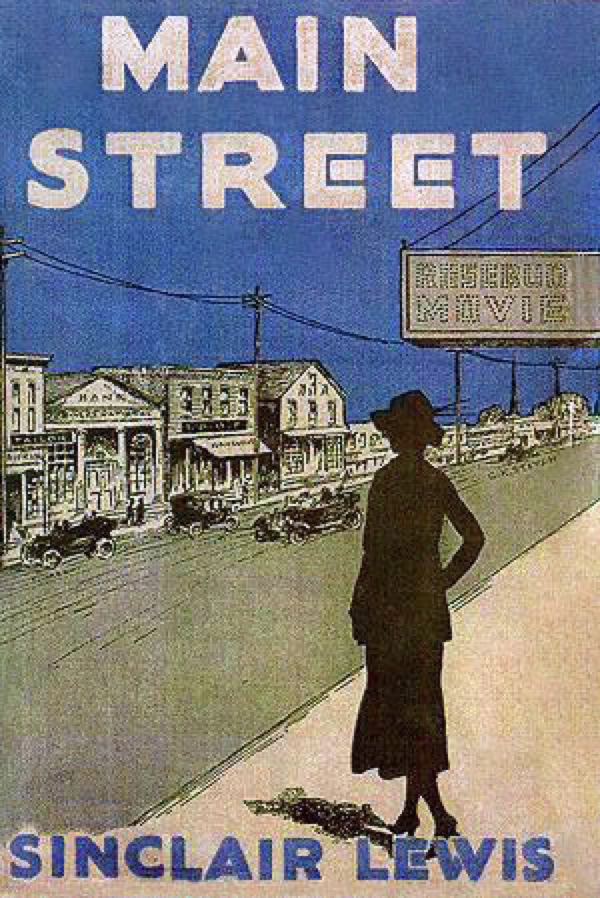

Main Street. Sinclair Lewis. 1920. 924 pages (Libby Ebook)

Our Williams Court Book Club 2, has scheduled a series old classic novels, most of them quite lengthy, for the next few months. Some must feel that their education in literature has been deficient, as mine certainly has. We start with this vivid but dismal picture of the boredom, hardship, uncertainty, and loneliness of life in the early twentieth century small towns and rural expanses of middle America, specifically in northern Minnesota, in the decade of 1910s. It is made to seem doubly problematic for Carol Milford, the new bride of one of the town’s three doctors; she was formerly a sophisticated educated librarian in St. Paul. As she adapts to her new role and environment in the fictitious Gopher Prairie, modelled after the author’s home town, she runs into a brick wall in her multiple attempts to institute the minutest liberal changes in the very conservative mindsets of the denizens, let alone any of her grand schemes to convert the town into a socialist artsy utopia with equal rights, women’s voting rights and free speech. The contrasting ambitions of Carol and her husband are dramatically played out in a spiteful escalating quarrel that threatens their marriage, and then on observing his advanced surgical skills, primitive by modern standards, her admiration and devotion is rekindled for a while. But later she departs with their toddler son for cosmopolitan Washington D.C. for almost two years before returning to grudgingly accept the staid conservatism of Main Street, Gopher Prairie, almost equally disillusioned with Washington society and politics.

The political atmosphere of the time is alluded to repeatedly with suspicion and hostility to all Germans and anything Germanic and bitter societal divisions over socialism and the new-fangled Russian Revolution. There is an abundance of circuitous dialogue, as everyone seems to be belligerently opinionated on the outside and hesitant, self-doubting, and insecure on the inside -except for the dogmatic bombastic, nosy and self-righteous Baptist preacher and his wife. Almost everyone seems to want to conform but refuses to compromise.

There is no very vulgar language and no explicit description of sex, although one character is ascribed characteristics that would make any modern readers think that he is gay and he is described as ‘queer’ a word that did not have the same connotation 100 years ago. And he assiduously tries to seduce some married women including Carol; there are many hints of extramarital affairs. The age-old practice of blaming the victim in a sexual scandal, particularly if a woman, is graphically illustrated by the case of the school teacher who is driven out of town, accused of immoral behaviour by her political and religious opponents. Paranoid intrigue, indignant self-righteousness and vicious gossip prevail in many of the characters.

The writing is dominated by dialogue rather than narrative and even unspoken thoughts are mostly enclosed in quotation marks, which can be confusing. I found a lot of the writing unnecessarily wordy and the ideas expressed were often vague and vague social constructs.

There are a few memorable quotes and descriptions. “Carol was discovering that the one thing more disconcerting than intelligent hatred is demanding love.” Rabbit and chipmunk tracks in snow are called hieroglyphics.

There are a few errors and puzzling obsolete words like ‘Jocosity’. One would think that after more than 100 years, errors such as repeatedly referring to Baptist clergymen as priests could have been corrected in newer editions. (I have never heard of a Baptist priest.) And spellcheckers could correct the references to the famous 1880s atheist as Robert. J. Ingersoll. (He is universally referred to as Robert Green Ingersoll.)

I am ambivalent about recommending this lengthy tome, but will be interested in the other book club member’s assessment of it.

⭐️⭐️⭐️