When I saw a review in The New Yorker, the title alone was enough to entice me to put a hold on this book at the Ottawa Public Library where it was still on order.

The China-born Distinguished Research Professor of Biology at Central Washington University provides an extensive scholarly discussion of the universality of lying and deception. Prevalent in the living world from lowly bacteria, viruses, and fungi that mutate to deceive hosts and and their siblings and thereby increase their propagation chances, to Homo sapiens, with a huge number of examples from the study of many species, lying and cheating seems to be universal. Most of the cited examples are erudite but interesting revelations about reptiles, birds and mammals and how they communicate both within species and across species lines. I now understand why some barn swallows I observed as a preteen seemed so protective of their nests and mates.

Two “Laws” of Lying i.e. falsifying honest messages in communication and exploiting other’s cognitive loopholes or blind spots which are biological foundations for lying and cheating respectively, are proposed, although I think the word “laws” would be better called “methods” or “types”

It takes either remarkable foolishness or an admirable dedication to scientific discovery to spend thirteen years studying the pheromones secreted from the anal glands of captive upstate New York beavers as the author did. But that showed that those pheromones were useful to the male beavers to identify kinships and avoid wasting resources on others, even if born to his allegedly monogamous mate.

The handicap hypothesis is applied to explain the existence of moose and deer antlers, peacock tails, and bright colours of male birds i.e an individual who can afford to show off such wasteful displays must be a potentially good mate. And the same handicap principle is applied to humans who signal fitness by, for example, giving nonreturnable expensive engagement rings of no other intrinsic value, or sporting expensive watches or cars, a la Thorsten Veblen.

Emmanuel Kant, and his categorical imperative to always, under all circumstances, tell the truth comes in for some criticism as Sun, in the final chapter waxes philosophical in distinguishing three types of lying and their moral implications, coming down on the side of consequentialist moral philosophers.

There is considerable overlap here with the content of David Livingston Smith’s 2004 book “Why We Lie” which I read years ago and many of the psychological phenomena, some old and some new to me are discussed to explain why we are easily deceived. But this is in the updated context of internet communication and especially AI which greatly facilitates the propagation of lies.

I have encountered my share of pathological liars and cheaters. The most memorable were a devout Anglican couple at whose hobby farm I spent many happy hours in the 1980s. The man was supposedly a foreign-trained pathologist until he was found not to be. Years later, he obtained a part-time job as a pathologist at a teaching hospital until a background check by the department head showed that he had had only one year of medical training.

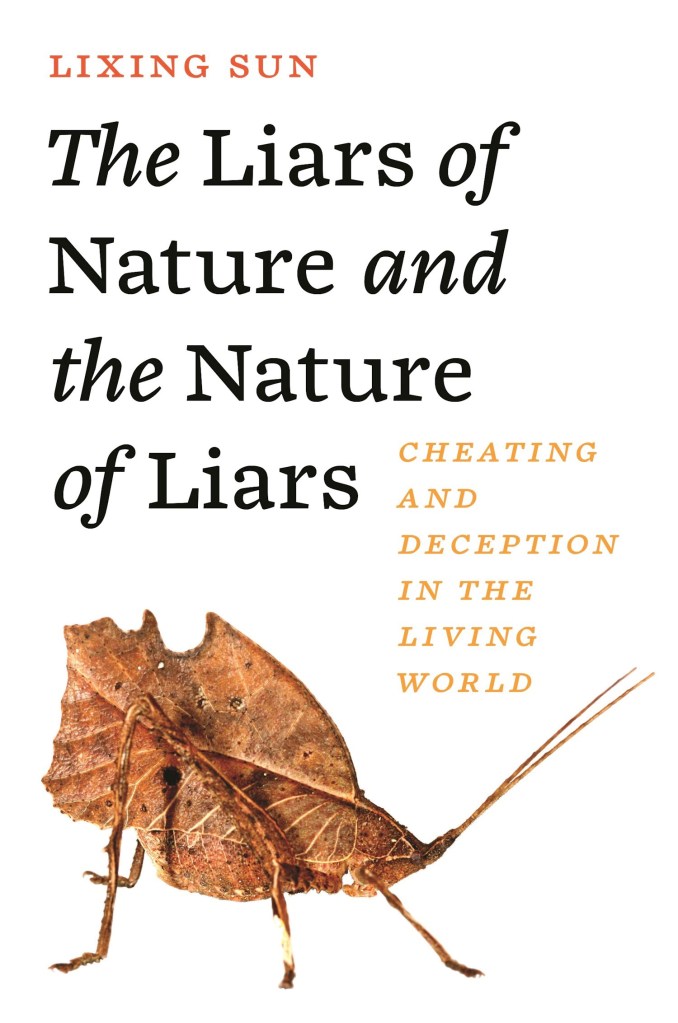

A quibble: some of the black and white photographs are fuzzy and contribute little to the narrative.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️/10

Thanks, The New Yorker.