From the author of the engaging and informative 2016 “The Genius of Birds” comes another delightful discourse on a single amazingly talented and diverse order of avian life.

First, my personal encounter with an owl. One spring day as kids, my brother and I discovered a huge nest high in a beech tree; we climbed an adjacent tree to peer into it. A startled young great horned owlet fluttered to the ground apparently unharmed, but not yet able to fly. (According to Ackerman, great horned owls do not build tree nests, so this must have been a hawk or turkey vulture nest commandeered by the owl family.) We wrapped her in a coat and took her home, housing her in a chicken coop in the attic of the farm shed. We discovered that she didn’t care for fish, but liked to bite our fingers, so we wore leather gloves when feeding her. Thus we inadvertently joined such luminaries as Florence Nightingale, Theodore Roosevelt and Pablo Picasso in raising a pet owl although ours was never friendly and we only had her for one summer. We fed “Hooty” all kinds of game that we hunted, from groundhogs, rabbits, and squirrels to various birds. The excrement and regurgitated pellets of fur, feathers and bones created a lasting stench, permeating our clothes. As she grew to a wingspan of almost six feet, a size that only females grow to, we took her out for progressive flying lessons from increasing heights, returning her to the coop when she fluttered to the ground at further and further distances. When we took her to the peak of the barn roof one day for her lesson, she simply took off silently over the horizon. I doubt that she survived long in the wild without the hunting skills her parents would have taught her. According to Ackerman, great horned owlets spend six months learning hunting skills from their parents after fledgling before striking out on their own. So began my lasting fascination with, and love of, owls.

Some of the observations in this book are esoteric in the extreme. Marjon Savelberg, a classical musician who studies owl vocalizations claims that she can look at sheet music and hear the song and can, by seeing the spectrograms of owl vocalizations, hear the distinctive calls of individual birds. This seems like an acquired form of warped synesthesia, but many owl species also have the ability to “see” and locate prey from sound input into their relatively massive asymmetrical ears, using not just echolocation, but echo 3-D reconstruction of an image. And now, using terabytes of data and AI, Savelberg can correlate the recordings of individual owl’s vocalizations with their observed behaviour. Place neurones in the hippocampi of owls give them a durable mental map of the territory they fly over. Some owl species make Peyton Place look virtuous with unfaithful longterm mates and constant mate swapping while some adopt unrelated orphaned owlets in what looks like owl altruism; others sometimes abandon their own offspring.

Some of the narrative gives anthropomorphic attribution of human emotion to the birds, such as the grieving sounds of owls who lost their tree nests to a forest fire. But there is little doubt that owls, perhaps more than most birds, are endowed with a rich emotional repertoire, from anger, jealousy, and fear to elation, love, and grief. And there is no doubt that owls and some other birds use deductive reasoning to ‘read’ the minds, intentions, motivations, and emotions of friends and foes alike, a theory of mind that was once thought to be unique to mammals, and particularly humans. It seems that almost no mental or physical feat is unique to humans, except perhaps the purposeful use of fire and communication via written languages.

There is documentation here of a far greater variety of owls than I was was previously aware of, from the sparrow-sized Elf Owl on up to the Great Horned. The small Saw-whet owls are ubiquitous in North America, but seldom seen, as they are extremely well camouflaged to blend into their environment. I can’t recall having ever seen one, but I have on several occasions seen a murderous murder of crows loudly harassing and attacking an almost invisible sleepy owl during the daytime.

This book is almost as revealing about the huge number of owl keepers, Owl Preservation Societies, and owl researchers as it is about the birds. From mythical Athena’s Little Owl to Harry Potter’s pet Snowy Owl, Hedwig, owls have played an important part in human mythology and several religions. Some modern workers aim to rehabilitate injured birds, others train and raise infant owls who have imprinted on humans to become ambassadors to educate school children and the general public about these unique creatures. Such education is important to conserve owls. During the Hindu annual Festival of Lights thousands of owls are killed in a misguided rite to bring good luck. “Hooty” never imprinted on us, being all antagonistic owl from the start to the end of our relationship.

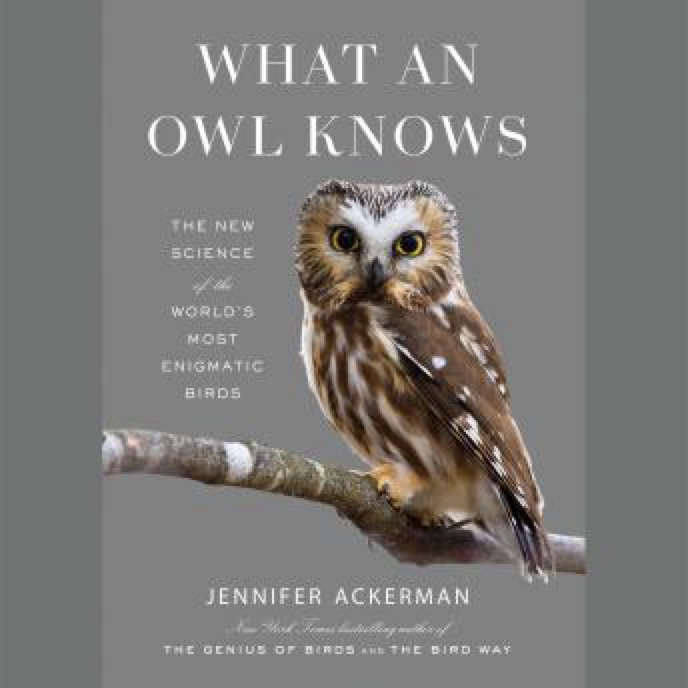

Both the coloured and the black-and-white photographs of owls are just delightful additions to the narrative of this book. Missing these with their strange face discs and piercing eyes would be a significant drawback of listening to this as an audiobook although it is available in that format.

Highly recommended for all nature lovers.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Thanks, Goodreads.