What is your career plan?

My working career is over. My aims now are to stay vertical and ventilating as long as possible and to be of as much use to friends and relatives as possible for as long as possible.

What is your career plan?

My working career is over. My aims now are to stay vertical and ventilating as long as possible and to be of as much use to friends and relatives as possible for as long as possible.

The fictitious protagonist of this story is a mischievous Jewish boy born in 1932 in downtown Montreal. From the first paragraph it is clear that he is not a conformist ordinary school boy. In Part I, heavy-drinking Mr. MacPherson, a teacher at the downtown Montreal Jewish school, finally becomes so enraged by Duddy’s antics that he breaks his personal principle to avoid corporal punishment of the unruly teens and applies the strap to Duddy. This revelation just sets the scene for what is to come.

An ambitious scheming dreamer, there is no doubt that Duddy, had he been born later when every personality quirk has become medicalized, would have been labelled as having ADHD, and perhaps as being on the autism spectrum. And as the story progresses, with his many enterprises thriving and then failing, one could also see Duddy as bipolar, alternately manically scurrying about chasing women or lying in bed for days with lucid disconnected dark dreams, thinking of suicide. A manipulative liar with laughable schemes to make money, he doesn’t hesitate to deceive friends and business partners alike. He always seems to have enough money for cigarettes and lots of booze to blot out his feelings of despair and dope his friends and relatives into supporting his schemes and lending him money. When all of his businesses fail, at one point, Duddy declares bankruptcy and resorts to driving a taxi for his father, all before he turns twenty. He sets an epileptic friend up as a driver for one of his businesses, with predictable results.

Usually just one step ahead of creditors, he drives taxi, sells illegally imported pinball machines, delves into real estate, dreams of developing a resort, produces and distributes movies made from camera recording of bar mitzvahs and weddings, and buys and sells scrap metal. He gets mixed up with an American heroin dealer and towards the end of the story, forges a cheque to finally purchase his dream resort lake property. To add to the diagnoses in the modern DSM -IV diagnoses that I discussed above, he would certainly qualify for the label of psychopathic personality disorder, but like many psychopaths, he can turn on the charm to get what he wants. As the author portrays him he is made to seem likeable to the readers.

Most of the story is concentrated on Duddy’s late teen exploits as a hustler and con artist

The picture of the striving Jewish families of the 1940s Montreal and of that city’s unique culture is interesting and detailed even though most of the families are depicted as highly dysfunctional. There is more than a hint of stereotyping Jews as money obsessed hard bargainers in all of their enterprises. There may be a grain of truth in this in that era; as a preteen, I recall the Jewish man who visited the farm to bicker over the price of scrap metal he was collecting. For the time when the book was first published the frank discussion of sensitive sexual issues and the loose mores must have been a bit avant garde. The foul language is confined to the conversations of the characters the reader would expect it from. The writing is mostly in short terse sentences and, like most of the conversations, often incorporates quirky humorous turns. It is as though the author is leading readers into the short attention span ways of the protagonist.

I quite enjoyed this old Canadian classic that had somehow previously escaped my attention.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Thanks, Williams Court Book Club II.

What do you do to be involved in the community?

My community is the whole world, although I no longer travel much. I connect with local people for bridge games and some dining out, keep in touch with a host of friends on four continents on Facebook, and volunteer at a curling club in the winter and at an innovative regenerative farming project in the summer. I belong to a group of old men who meet weekly on Zoom to solve all of the world’s problems in one hour!

I always vote. One shouldn’t complain about what our politicians are up to if you haven’t voted. I research my choices carefully, but I like to throw the pre-election pollsters for a loop by telling them I will vote for the Communist Party candidate or the one from the Marihuana party. In the past I have asked the first candidate to knock on my door to put a sign on my lawn as it acts like pest detergent for the others that come by.

Do you vote in political elections?

In this massive tome, a Yale professor of American history outlines the complicated life history of J. Edgar Hoover, the quintessential government man and Director of the FBI from 1924 at age 29 until his death in 1972. Her opus is even longer than the above pagination would suggest as the hardcover edition I read is set in a small font on 6” x 9” pages.

Hoover was the prototype Washington insider. Born there, he was educated at it’s elite, segregated, all white Christian schools, then at George Washington University where he led the Kappa Alpha fraternity which supported segregation and the KKK. He graduated in 1917, then worked for four years cataloging and filing at the Library of Congress. Thereafter that experience was used in the Justice Department where he quickly rose to the deputy and then full director positions at the new FBI. Obsessed with cataloging and files, he kept files on and prosecuted labor leaders and early on organized the secret detention and deportation of Germans. His illegal roundups and deportations included radicals and communists. He joined the Free Masons and admired the right-wing John Birch Society.

The remit of the FBI expanded in 1934 under Roosevelt, and it was involved in the capture of the notorious gangster John Dillinger. Killings and veiled authorization to torture captured suspects and witnesses and deny them legal representation became a secret but common modus operandi. Hoover developed a PR initiative with Hollywood moguls and newspaper editors, offering tours of HQ to offset his investigation of Hollywood stars and media types as communists. By1938 the FBI had secret authorization to collect information on American Nazis, Communists and fascists, with a fuzzy alliance with the ACLU and NAACP that gave it the facade of being apolitical. During WWII, there was a fourfold increase in personnel with extensive wiretapping and spying on innocent citizens that included Eleanor Roosevelt whose hotel room was bugged in an effort to discredit her liberal influence. A file on her alleged dalliances during her husband’s presidency was maintained.

In 1945 Hoovers authority was challenged when president Truman replaced Wild Bill Donovan’s Office Of Strategic Services for foreign intelligence, losing to the new CIA, but he managed to limit the later’s scope to foreign affairs, thus maintaining total control over domestic security services. After WWII, much of the focus of the FBI was on the perceived communist threat with exposure of of senior government men and Hollywood moguls as Soviet agents, trying to outdo the exaggerations of the danger to national security of flamboyant Senator Eugene McCarthy. He saw communists, Nazis, and insurrectionists, real or imagined, everywhere. He claimed to expose many senior government officials as Soviet agents with some success, with outing of Alger Hiss at the State Department, and collected information on Kim Philby, Donald McLean, Guy Burgess, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, often using secret and illegal means of obtaining the evidence.

The FBI also provided minimal results in a less-than-enthusiastic attempt to stop southern lynching and enforce voting rights because doing more conflicted with Hoover’s racism. But the failure of these efforts was also abetted by racist southern Democrats, police and judges.

Agents also provided duplicitous cooperation with the NAACP in the late 1950s southern integration dictates following the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, playing both sides, genuinely attempting to enforce federal law while trying to remain on friendly terms with southern segregationists. Hoover’s book, Masters of Deceit, an anticommunist manifesto was touted by William F. Buckley, the John Birch Society, and Barry Goldwater. Wild extremist conspiracy theories are not new, as amply documented by the Birch Society followers that Hoover had to reluctantly distance himself from in the early 60s. His two-faced endorsement of Johnson’s Civil Right’s Bill is typical of the ultimate political survivor and blackmailer. While seemingly enforcing the provisions for Johnson who had waived the mandatory retirement age for him, his racist misogynist conservatism ensured that he did as little as was politically necessary.

Hoover was overly antagonistic to to the Kennedy administration after supporting Nixon in the 1960 presidential campaign but had enough dirt on the Kennedy clan to ensure that they would not fire him. The confusing role of the FBI in 1962 with the CIA and organized crime bosses Robert Maheu, and Sam Giancana to assassinate Fidel Castro, and their support for the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba was hidden from Hoover by his own agents at the time.

In 1963 Hoover publicly labelled Dr. Martin Luther King as “ the most dangerous Negro in America”, wiretapped his home, office, and numerous hotel rooms where he had many orgies.

Throughout his career he maintained rigid control over every aspect of the all male agent’s lives including work attire, hair length and much of their social lives. He was constantly at loggerheads with his younger boss, the Attorney General Bobby Kennedy in the Kennedy administration over these dictates. A Nixon pal and Johnson neighbour, he maintained his job by obtaining secret secure information on John Kennedy’s many affairs, some with women associated with gangsters.

In 1965 an aging Hoover could only think of the New Left antiwar students, the mostly white Students For A Democratic Society and Stokely Carmichael’s mostly black Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as insurrectionist communists, and investigated them as subversives a la 1950’s McCarthy hearings. Later he targeted the Black Panthers, the only avowed Marxist group, with the same invective and subjected them to surveillance and repression with anonymous letters, press releases, bugging and outright lies to the media.

In later years, rising conflict with his ally Richard Nixon in his presidency centred on when he would retire and who would replace him. But Hoover also had the upper hand here as the master blackmailer, to remain in power and Nixon could not bring himself to fire his pal. He died suddenly while still in office in 1974. A whole chapter is devoted to the accolades of politicians, conservative allies and hypocritical liberal opponents alike after he died. This reminded me of Garrison Keilor’s humorous quip: “They say such kind things about people at their funerals that I am sorry that I will miss mine by a few days.”

During his entire his 44 years as Director the entire FBI maintained a misogynist and racist stance with women and blacks employed only in low ranking menial jobs. He also targeted gays and atheists even though he was himself almost certainly a closet gay, living his whole adult life with his Associate Director and constant companion, Clyde Tolson. It is true that in the past, gays were often at risk for blackmail by foreign agents, a phenomenon that fortunately has largely disappeared. But throughout history to the present day the most vehemently homophobic men, such as Hoover, are often themselves closet gays, and Hoover was one the most outspoken homophobic men of the century.

One remembers history more vividly if one has lived through it. I lived in the U.S. for three years, under three presidents- you can guess the years- and was acutely aware of the turmoil in their politics at that time. The atmosphere in New Haven where I lived and studied, in the aftermath of the murder trial of the Black Panther national chairman Bobby Seales there was tense, with lots of protests and violence and made me pay more attention to politics than I would have otherwise. But the account in this book is very different from what I recall in the news at the time, and undoubtedly more accurate. There is little doubt that if Hoover had been born in 1965 instead of 1895, he would now be an ardent Trump supporter.

This detailed scholarly dry account is very informative and provides important lessons for the current era, even though it is very American-centric. It is also, like this review, a bit chronologically disjointed. But I hope my sketchy review does not deter people who like history from reading it.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Thanks, The New Yorker.

Have you ever been camping?

Many times. Mostly in northern Ontario at fishing camps or bicycling.

This third novel by the British midwife converted to full time writer begins in July 1938 and 57 chapters later ends a WWII begins. postscripts detail the postwar lives of the main characters.

British foreign correspondent for The Chronicle, who becomes part time detective, Georgie Young in Berlin relates the details of the city and the buildup to the war as the rest of the world ignores her warnings and documentation of Nazi atrocities in fifty seven straightforward, numbered and dated chapters. Among the most graphic details of Nazi horrors, is the description of Kristallnacht, (the night of broken glass, November 10th, 1938) when a coordinated Nazi roundup of Jews, the disabled, homosexuals, and Jehovah Witnesses should have alerted the rest of the world to their depth of their debauchery.

As the story progresses, the adventures become less and less realistic, but still gripping. Many chance encounters and harrowing escapes seem designed to hold the reader’s attention like a cheap spy novel, rather than as anything that could possibly happen. This includes the eventual romance of two of the rival British foreign correspondents posted to Berlin. I

The writing is certainly engaging and the plot is complex but not hard to follow. There are hints of support for early feminism in the misogynist world of journalism and the heavy drinking for which the crowd of journalists is known is not ignored. Sexual innuendo abounds as Nazi officials proudly display their foreign conquests, but there is no graphic pornography.

Among the memorable quotes is this:

“Hence the need for a foreign press, and the hundreds of underground pamphlets and newspapers pushing their heads up like daisies through the manure bed of propaganda.”

In the vast number of historical novels based on WWII, this is one of the better ones I have read, perhaps on a par with Kristen Hannah’s The Nightingale. But my appetite for this specific genre is dwindling.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

I have no one to thank for recommending this book to me, as no one did. When I sent a draft off this review to my wife for comments and corrections, as I usually do before posting, she pointed out that the book she had actually recommended was titled The Girl From Berlin-same genre, different author, different plot, slightly different time frame, similar theme. My mistake.

What topics do you like to discuss?

It largely depends on who I am conversing with but I enjoy discussing current affairs, anything related to science, and history. We are told to avoid discussion of politics, sex, and religion with people we do not know well, but those are never off the table if someone else introduces them.

Describe a risk you took that you do not regret.

When I left a secure position as an associate professor at Western, after being denied a promotion to full professor, I had concerns about my future as a private practitioner dedicated solely to hepatology. But my research, teaching, and patient care flourished without the restrictions of university and hospital politics, And it proved at least as remunerative as practice within academia without all the stress and boring committee meetings. No regrets.

I am thrilled that all four of my grandchildren have become avid readers, so when the 12 year old suggested this book, said to be for “14 and up”, I felt I owed him the courtesy to check it out. I expected something light and fluffy, not a dark graphic novel composed entirely of cartoons set in a black ghetto in an unidentified city.

The loose plot is of one boy in the world of street gangs warring over territory for drug dealing and includes a lot of street gang lingo, shootings, and revenge. It realistically includes the broken families and lawlessness of the setting. But it also includes some magic as the lead character plans to revenge the shooting of his older brother, uncle and father by talking to them for advice.

The artistry is more like graffiti than anything closely attached to the plot, but that is probably intentional. All in all, a dark but interesting and very uniquely American three hour read.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Thanks, Kiran.

In his distinctive voice, the Canadian advertising executive and host of CBC radio’s Under The Influence builds on a common observation. Big mistakes often become positive turning points for the individuals involved. Not limited to those in the advertising industry, he delves into the lives of entrepreneurs, Hollywood moguls, inventors, sports stars, and entertainers whose apparent massive mistakes changed their lives forever for the better.

I found some of the 20 short profiles mesmerizing, and others a bit confusing. Among my favourites is the story of how a massive overestimate of the demand for Thanksgiving turkeys lead to the timely creation of the very profitable Swanson TV dinner enterprise, the uncanny mistake of getting drunk and hungover making Seth McFarlane miss his plane on 9/11, the second one that flew into the World Trade Centre, and the creator of the Old Farmer’s Almanac leaving the predictions for July, 1816 missing, with a kid adding in snow and sleet as a joke, which proved accurate. I won’t spoil the read for others by detailing other unlikely but true tales.

Reading this engaging, carefully researched book made me reflect on my own many mistakes and pick the one that best fits the category. That would have to be applying for a promotion to full professor in academic university medicine at The University of Western Ontario. That was denied by my duplicitous colleagues, some after assuring me that they would support me. That led me, with my wife’s encouragement, to leave the academic world and set up a private practice dedicated wholly to liver diseases, the first in Canada, while retaining hospital privileges, based on legal precedent. It proved to be much more relaxing, less restrained by university and hospital rules, and at least as remunerative as full time academic practice. I set my own schedule, hired my own staff, and attended few committee meetings. I conducted more research and teaching with much less stress for the next 15 years than I would have ever done as a full professor, and enjoyed it far more, right up to when retirement called.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

How do you unwind after a demanding day?

Usually I would just go for a long walk, preferably in the forest. “ Forest bathing” can work wonders on my psyche.

How do you use social media?

Obviously, I use this site to publish my book reviews. In addition, I use Facebook to keep in touch with many friends. I use Safari to find answers to questions that pop into my head, And google maps to plan trips, mostly to local spots. I play Scrabble on line with a few friends, subscribe to three magazines online and borrow ebooks or audiobooks from the library. Since Covid, I have used Zoom to connect into three educational outfits. I guess some of these uses are not strictly social media, but more just internet use.

What place in the world do you never want to visit? Why?

The interior of Antarctica. I have been as far as several stations on the Antarctic peninsula, and greatly enjoyed that but the loneliness, endless whiteness and desolation of anywhere closer to the South Pole would be pretty boring.

This is the very iconoclastic rant of an Hungarian Jewish physician and prolific writer and speaker working with the downtrodden population of lower east side Vancouver, mostly with drug addicts. His previous books and his film “Trauma Awareness” have been very well received and apparently are sort of background material for this one. (I have not read or seen these.) He shows throughout the book distain for the capitalistic, consumerist ‘toxic culture’ of the subtitle but only gives some tentative suggestions for society-wide changes needed in the last half hour of this read, including changes in educational institutions, medical and legal training and in so-called correctional institutions. His disillusion with communism in his youth, with American atrocities in Iraq, and with Israel’s cruelty to Palestinians no doubt colour his current opinions.

(Sorry, Dr. Mate, my iPad refuses to enter the diacritical e in your name) Mate’s definition of trauma as an internal response rather than external events that we have little or no control over is a little peculiar and leads to dissection of emotional responses to physical events ad nauseam. His definition of addiction is also complex and makes everyone fit in as an addict to something, but he counterintuitively relates it mainly to early childhood adverse events that fit with his definition of trauma. He does not indulge in the debate about whether or not there is such a thing as a mind, soul, or spirit separate from the molecules in one’s nervous system, as many philosophers do endlessly, but uses the word bodymind as a unity, not a dichotomy, and as an intricately interconnected entity. Later chapters suggest that he accepts that there are such entities as a soul and a spirit separate from the body, but what they are is vague at best, and no specific religion is endorsed, with just a hint of praise of Buddhism.

The modern biologic sciences are not neglected and he discusses subjects such as the effects of stresses on telomere shortening, epigenetic expression of genes and inflammation as a mediator of all kinds of diseases, often originating in changes in neuronal wiring and transmitters from trauma. Surprising observations such as that only 25 % of the increased longevity in Canada over yeas is attributable to health care interventions, that no genes for addiction have been found, and that loneliness is as big a public health crisis as devastating as the obesity epidemic seem to rest on solid evidence. Other accepted assertions based on social science association studies may suffer from the common problem of equating correlation with causation, and anecdotal observations e.g. that patients who develop ALS share a distinct personality, though not easily dismissed, are on shaky ground and not statistically analyzed at all.

There is a great chapter on the medicalization of childbirth and the need to revert to some more traditional practices in that field. At the same time, while critical of much of mainstream medical care practices, in this field and many others, He is careful to include disclaimers about not totally dismissing them and about not blaming victims who develop diseases that he believes are caused by their unwitting compliance with expectations of a ‘toxic culture’. The child rearing industry also comes in to severe criticism and the proliferation of parenting advice is referred to as the “parenting industrial complex”.

In chapter 23 rampant misogyny in a patriarchal society is alleged to explain gender discrepancies in incidence and severity of almost all debilitating diseases -but that, I note does not explain why women on average outlive men. In the next chapter, the author’s remote dissection of both Donald Trump’s and Hilary Clinton’s psyches is interesting but the conclusion that their personas are entirely explained by their childhood traumas as he defines trauma seems a bit simplistic. His penchant for analyzing the rich and famous without any need to meet them extends to our last two Canadian prime ministers and predictably he cites childhood trauma as the reason for most of their actions and beliefs. He seems to think that no one has had a happy childhood, and if they claim to have had one, they must be suppressing memories of abuse. The suppressed memories phenomenon is real but probably rarer than claimed by many writers. (What memories have I suppressed to recall mainly happiness and little ‘trauma’ in my childhood?)

Robin Williams’ suicide is traced to his insecurity, loneliness and bullying as a child even though he was aware that he was losing his mind and the autopsy showed that he had Lewy Body dementia, a disease that has never been linked to any mental stress or trauma. It is sporadic and labelled as idiopathic, a medical term for something of unknown cause. But almost nothing is of unknown cause if one follows all the links created here, mostly to childhood trauma.

This author shows a disturbing distain for and demeaning of mainstream medical advice, practices, and prognostications with selective documentation of miraculous recovery from apparently terminal illnesses. It seems odd that he never offers any opinion on the harm reduction strategies such as needle exchanges and safe injection sites for addicts, given his work environment.

Mate asserts that both higher than normal blood cortisol blood levels and lower than normal levels signal an unhealthy stress level, but ironically for someone whose book is titled “the Myth of Normal”, never questions how the margins of the normal or reference levels are set for this and many other ‘normal ranges’. One of my favourite beefs is when ‘normal’ is used wheree ‘average’ or ‘mean’ or ‘usual’ is the appropriate term as in weather reports of temperatures. For medical lab data, the normal or reference range is often set as what 95 or 98 % of what may be a highly unrepresentative population of hospital employees or university student volunteers has.

The therapeutic use of the ‘magic mushroom’ hallucinogenic psyllium is endorsed and he relates his use of it in a Peruvian ceremonial retreat. Yoga, meditation, and mindfulness practices are also praised. I will never condemn such practices, but they do not appeal to me.

In later chapters, healing, which everyone apparently needs, is described as a journey, not a destination. This leads to a long dissertation with fuzzy definitions of various mental exercises. Five levels of compassion are delineated with a lot of mystic opaque mumbo-jumbo and promotion of his own “Compassionate Inquiry” program that I found confusing.

Given the opportunity, there is no doubt that this author, on a panel to judge various phenomena, would invariably issue a minority opinion, rather than that of ‘conventional wisdom’ a term coined by the late economist John Kenneth Galbraith. But he provides sage wide-ranging counterintuitive and informative insights about our current economic, political, societal, and cultural milieu that made the read quite enjoyable and worthwhile for me.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Thanks, Mike I. and Pat C.

What is your favorite restaurant?

Close to home there is a great Italian restaurant called Viamarzo, that has a good selection of unusual combinations including lot of choices for vegans, and great wines at reasonable prices. We take guests there quite often and have never been disappointed.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

Probably as organic compost nourishing a growing sapling somewhere of my survivor’s choosing.

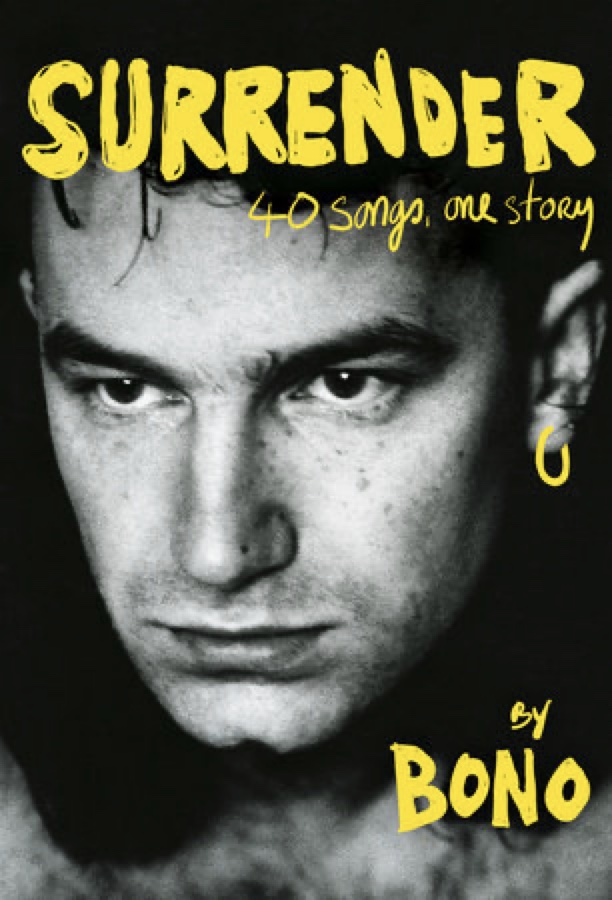

Surrender. Bono. 2022. 555 pages (Hardcover), 25 Hours (Audiobook).

Born in sectarian northern Dublin in 1960 to a Protestant mother and a Catholic father, Paul David Huston, nicknamed Bono by a childhood playmate, early on espoused a generic Christianity. But that Christianity rejects most of the St. Paul add-on doctrines dividing modern denominations, and is more like a moral code to live by as taught by Jesus than any specific religion. The god he prays to before every performance of his famous U2 band is seemingly capable of intervening in human affairs but is a bit ethereal and distant.

His mother died suddenly when he was 14 and much of his early life dwells on his mourning and insecurity as his distant father was unable to provide much guidance and/or praise. But he produced his first album of rock music at age 18, and soon thereafter established the famous quartet named U2 that stuck with him for the rest of his career to date, touring the world, playing to huge crowds and producing many albums. In later years, his music career was intimately interconnected with social and political activism, often incorporated into the lyrics. The impressive list of world leaders that he was and is on a first name basis includes Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachov, Tony Blair, Angela Merkel, Pope John Paul II , Nelson Mandela, Lady Diana, Condoleezza Rice, George W. Bush, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Warren Buffet, and Oprah. Too many famous modern musicians to list were or are his pals. Perhaps most notably they include Frank Sinatra and Luciano Pavarotti. I may have forgotten others but notably absent from this list are Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. His lobbying of movers and shakers contributed in a major way to such developments as the Good Friday Accord, the cancellation of billions of dollars of debts of poor countries to rich ones, making anti-retroviral drugs available and affordable to Africans, the end of the siege of Sarajevo, and action on climate change.

Bono’s Christianity apparently does not preclude overindulgence in alcohol and drugs, nor the liberal use of foul language, but he seemingly remained faithful to his childhood sweetheart wife Ali (or conveniently omitted mention of any affairs.) He admits to having an bad case of imposter syndrome with a strong belief that he does not deserve his fame and fortune, even though at times he comes across as having a Messiah Complex, solely responsible for saving the world. But for someone without a university degree, he demonstrates an immersive knowledge of literature and history. There is lot of navel gazing self examination about who U2 were and what they wanted in life with fuzzy distinctions between different messages they wanted to convey that were lost on me. But there is no doubt that Bono has been a positive force for good in the world over the last 45 years.

A few memorable quotes: “It takes great faith to have no faith.”

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you’re probably on the menu.”

“Living well, as someone put it, is the best revenge. Come to think of it, just living will do.”

There are a few interesting insights into the increasingly complex world of music production and distribution in the age of digital remakes, and live streaming.

Later chapters detail a mystical searching for the Other, the meaning of existence, with no clear answers and a continuation of doubt that I found to be ethereal. The whole book is chronologically and geographically disjointed jumping all over in space and time like an agitated drunk rock star, for no obvious reason.

As someone born before the Baby Boomers, my music tastes tend toward the 19 and early to mid 20th century: I have never been a U2 fan and have trouble even understanding the sometimes subtle differences in genres labelled as rock, punk, punk rock, grunge, pop, soul, hip hop beat, but I do admire the socially-directed lyrics of many of the band’s songs such as Bloody Sunday. That one was attacked by both sides of the Irish conflict, and is, if I am honest, the only one I knew about before reading this autobiography.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Thanks Ian G.

What’s the most fun way to exercise?

Horizontally in the nude with a nude partner.

If you could be a character from a book or film, who would you be? Why?

Tom Sawyer. Personable, persuasive, fun-loving, honest.