This author’s life began in 1956, the child prodigy of an English aristocrat and a Irish society lady in Cork, Ireland. But she became an orphan at age 12 and thereafter was raised by an absentminded uncle who allegedly, simply failed to provide anything and she became severely malnourished. She was educated in the summers in a ancient traditional Irish Celtic coastal community. The 75 page narrative of her early development, is at first a bit paranoid and self-pitying in tone detailing her insecurity and self-doubt, then reversed to tout her self assurance and intelligence as she is educated with a double major in botany and medical biochemistry at University College Cork, finishing a Masters degree course by age 21.

She developed an early love for all animals, and the outdoors, as well an appreciation of ancient customs and folklore. Sun-exposed potatoes were found to be a good topical cure for her warts. (Solanine, the chemical produced in sun-exposed potatoes is a powerful toxin if ingested, but also makes them extremely bitter.) The ancient Celtic rites of the Lisheen valley folk, such as needing to be introduced to scattered altars and using dew on shamrock leafs as beauty aids have a mystical, almost pagan aspect but blend seamlessly with the all-encompassing Catholic influence. Some practices such as using that dew to improve eyesight seem like pure quackery to this scientist and some plant based chemicals such as St John’s Wort are accepted as valuable medicines without critical supporting evidence. (It has dangerous interactions with many proven pharmaceuticals.)

It is not until page 76 that the plight of trees is even mentioned, and cutting them down is then described as an act of suicide. Thereafter the focus is largely on trees as she escapes from her self-pity and demonstrates her real brilliance as a concerned environmentalist.

She moved to Ottawa in 1982 to study plant hormones and get a Ph.D. at Carleton University then taught at the University of Ottawa for nine years. Then, a trophy husband in tow, she moved to a unique private experimental farm somewhere nearby. The claims she makes for the importance of her work are striking. “Trees have the neural ability to listen and think; they have all the necessary component parts to have a mind or consciousness.”

The sweeping assertion that an unidentified chemical from the hop tree “… revs up your major organs.. “ and “ …allows your body to make efficient use of medicines” would be seen as meaningless nonsense to most medical biochemists. It is true that many plant compounds change the rate of liver metabolism of certain other chemicals and medicines but that is as likely to be harmful as beneficial. She spent four days in a helicopter over a 200 square mile Texas ranch looking for a tree species that was possibly extinct, finally finding one tree, then claims that it was the only living one of that species in the world!

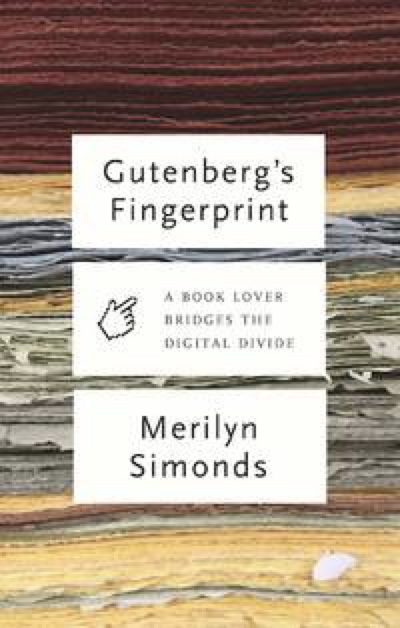

While this woman’s insights, perspective, and research findings are important and interesting, the whole book is infused with arrogance and self importance. I recall only one instance where she acknowledges the results of research of another scientist that she was not involved with. There are far too many instances of “I proved”, I found”, I discovered”, “my research showed”, etc. without acknowledgment of the contributions of others. Neither Susanne Simard’s “Finding the Mother Tree” nor Merlin Sheldrake’s “ Entangled Life” are mentioned although much of her research into forest life and fungi overlap with the content of those books. Who coined the term ‘The mother tree’ first? In her Acknowledgments, there are no other research scientists or environmentalists thanked. Even in the Suggested Reading, she cites six of her own works but no other acknowledged world experts in forest preservation such as Sir David Attenborough, Sheldrake, or Simard.

Part 2, comprising 94 pages delves into the ancient Celtic and Druid history and folklore of the message conveyed by 20 different trees and plants. Although this part is an interesting introduction to ancient Celtic culture, it’s claims are even less scientifically authenticated than those in the rest of the book. The discoveries of aspirin from willow and the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel in hickory trees are well known, Some of the other uses of trees and tree products, uncritically accepted by the author, such as divining for underground water with a hickory stick shaped into a wishbone lack any scientific validation. I recall this ancient practice being used in my uncle’s farm yard to locate where to drill a well, but they then had to drill down more than 350 feet to hit water. It may be pure witchcraft with witch hazel. The medicinal claims for the hawthorn extract that supposedly selectively dilates only the left descending coronary artery of the heart seems to me to be dubious at best. By the account here, elderberry extract is used medicinally to treat night blindness. I have become wary of any claims that some product “boosts” the immune system since it is extremely complex and prone to attack other parts of our bodies in the form of autoimmune diseases.

An interesting combination of autobiography and environmental science treatise, I am ambivalent about recommending this book. There are interesting perspectives and bits of information, but to glean them, you need to have both your lie detector and your bs filter in good working order, and on high alert.

⭐️⭐️

Thanks, Jeannie